Call it modern Mesopotamian claymation. With the help of the latest Artec3D equipment, archivists and instructional technologists have teamed up to produce 3D scans and models of the university’s collection of 4,000-year-old Sumerian cuneiform tablets.

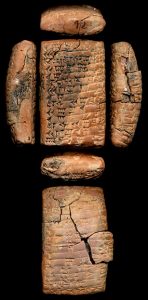

Cuneiform, one of the earliest systems of writing, was developed by the ancient Sumerian people of Mesopotamia. Recognizable for its wedge-shaped marks on clay tablets, cuneiform was created using a blunt reed to press a design into the wet clay.

şÚÁĎÍř’s collection comprises 48 cuneiform tablets, which document the trade of goods like silver, fish, flour, and sheep. “Our cuneiform tablets and most of the tablets that you find are economic texts like receipts and accounting records,” said Sarah Keen, university archivist and head of .

Original cuneiform from şÚÁĎÍř’s archives

The artifacts are often used in şÚÁĎÍř classrooms as teaching aids for courses in , and related subjects. “They allow students to study the primary goods that were traded and what fueled these economies. [A tablet] gives you an entrĂ©e into some aspect of that society,” Keen added.

Instructional technologist Doug Higgins partnered with şÚÁĎÍř’s conservation technologist Allison Grim and Keen on the project. The team was joined by Ian Roy from Brandeis University and Jordan Tynes from Wellesley College.

“Three-dimensional scanning, modeling, and printing will allow us to bring the archives out of the boxes and to the şÚÁĎÍř community both locally and globally,” Higgins said. “We have the ability to share the artifacts digitally, or to bring the [3D-printed] models up the hill and have a closer study of the items within the classroom without fear of them being damaged.”

Handheld 3D scanners work by gathering a steady stream of photographs as the object is rotated. The scanner then uses software to stitch those photographs together in order to generate a model that measures to a tenth of a millimeter for accuracy.

The digital cuneiform models have already proved useful as educational tools. has used the models to supplement his anthropology course, Comparative Cosmologies, by projecting the models onto the 32-foot wide screen of the .

“My students had the opportunity first to handle the cuneiform, hold them in their hands, and see what they look like,” Aveni said. “Then we did a projection in the visualization lab of the 3D scans so that you could rotate them, spin them around, and look at the flip side. It gives students another perspective of the artifacts they’ve seen. These are marvelous teaching aids.”

The success of this cuneiform scanning project leaves Higgins hopeful for others like it in the future. One potential application of this technology is the 3D scanning of şÚÁĎÍř faculty research. Higgins envisions professors capturing 3D scans of archaeological sites abroad and bringing the images back to share with students.

He said, “I’m excited to see what we can do next.”

Check out the 3D models , and give şÚÁĎÍř’s cuneiform tablets a spin.